Tilted Arc V2

Please allow 10 working days to process before shipping

Garment Dyed - Khaki Short Sleeve

100% Ring Spun Cotton

Profits to: Hungry Monk Rescue Truck & Woodbine

Richard Serra v. the Office of Operations, GSA and subsequent appeals and lawsuits became some of the more notorious cases in the history of art law in the United States - addressing the complex issues of artist's moral rights, state censorship, and the limits of free speech in a public art context.

In 1972, the General Services Administration (GSA) established its Art in Architecture program, which mandated that one half of one percent of all new federal building projects budgets be allocated to the incorporation of publicly-sponsored art. In 1979, the GSA asked Richard Serra to create and install a public sculpture on a plaza adjacent to a federal office complex in lower Manhattan, a service for which Serra would be paid $175,000.

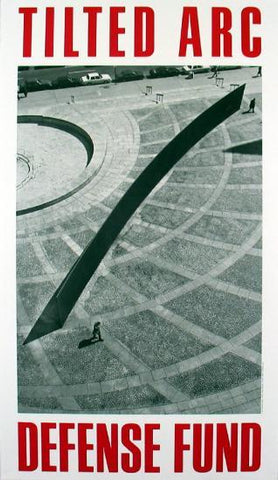

The GSA had a history of commissioning well-respected sculptors: Both Claes Oldenberg's Batcolumn in 1977 and Alexander Calder's Flamingo in 1974 were paid for by the GSA and installed in large outdoor public spaces in Chicago. After about a year of interviews, drafts, and reviews by both art-world appointed civilians and government officials, Serra installed Tilted Arc, a 120 foot long by 12 foot high curved steel structure, in the middle of Federal Plaza in New York City.

Unfortunately, nothing was done to prepare people for the arrival of the steel sculpture and the reaction of office workers to the piece was negative: it was immediately seen as ugly, oppressive and a ‘graffiti catcher’. Two petitions seeking the removal of the piece quickly gathered 1,300 signatures.

The GSA stood firm, arguing that the 1,300 signatures on the petition represented a minority given that there were 10,000 employees in the building. However, the direction of the GSA changed dramatically in 1984 with the arrival of a new Republican-appointed regional administrator, William Diamond.

Diamond arranged for a three-day public hearing about the possibility of relocating the work, and appointed himself head of a panel of adjudicators. At the public hearing 180 people spoke, including Serra, who pointed out that the work was site-specific and would not function as an artwork if moved elsewhere. He also flatly denied that it interfered with social use of the plaza. In all, 122 people, including many eminent figures from the art world, spoke in favor of retaining the piece, while only 58, mainly those working in the nearby offices, testified against it. Despite these figures, the panel voted to relocate Tilted Arc. Serra sued, but the courts ruled that the GSA owned the piece and could do what it wished with it.

The sculpture was finally removed on March 15th, 1989. Cut into three parts, Tilted Arc – or, rather, what remains of it – is stored in a warehouse. The artist regards the work as destroyed because it was removed from its intended site. He also noted that, in disregarding his argument and considering the work as movable, the GSA had made the work ‘exactly what it was intended not to be: a mobile, marketable product’.

To this day Serra insists that the work can never be installed anywhere other than the Federal Plaza. And although the GSA has made attempts to reinstall the sculpture at an alternate location, organizations have been reluctant to go against the wishes of the artist. As a result, Tilted Arc has remained in storage for the last 30 years.

In this atmosphere, the exhibition, “After Tilted Arc” at Storefront for Art and Architecture was an attempt to reframe the issues, to look at the problems anew through the creative and/or critical work of artists, architects, and writers. Twenty-eight drawings, sculptures, and statements were mounted in the small gallery, from one-page typed statements, to beautifully crafted models of the site.

Although Storefront was careful to state in all publicity that the exhibition did not advocate the removal of the Tilted Arc, it seemed that, from an art world perspective, the issue was not open to debate: we were supposed to stand together in defense of Serra, united against the forces of ignorance. In retrospect, there was some validity to the perception that the exhibition was hostile to Serra. In the Xeroxed publication (that served both as a request for proposals and a catalogue) we invited artists to:

Explain, narrate, or invent the public mythology that Tilted Arc can provide for the average and sophisticated viewer.

Redesign the plaza or Tilted Arc to provide a synthesis of the needs of the public and the Arc.

Propose a new public artwork for the plaza:

The Federal Building’s employees had no more interest in learning from the “experts” than the experts had in learning from them. Egged on by the GSA’s Regional Administrator, they vented their bile on the hapless Arc, seeing in it a symbol of their powerlessness. They had no idea what the artists and curators saw in the piece. Neither side was listening.

The majority of the artists suggested ways to redesign the plaza of the sculpture to accommodate the art and its audience.

Michael Sorkin’s Serra in an Expanded Field, like several other projects, suggested that the Federal Building, not the Arc be removed. His humorous drawing of the Arc in a huge open space pointed out that as long as public commissions are sited in bland architectural environments, the art can never solve the basic problems. One percent for art can never compensate for the 99% spent on oppressive design. For The Feminization of the Tilted Arc. Nancy Spero painted one of her (feminist) narrative scenes on the model of the Arc. Although Spero’s painting harmonized with Serra’s soft curve, it pointed to the grand, macho gesture.

This exhibition at STOREFRONT does not advocate the removal of Tilted Arc. Rather, like other exhibitions, we have undertaken at STOREFRONT, (Adam's House in Paradise '84, and Homeless at Home, August '85 - March '86), public debate has created a foundation of ideas. The immediate situation requires intelligent action; the inherent cultural issues demand public resolution; and STOREFRONT wishes to inject a reasonable voice into the debate without simply advocating a specific position.

Please read the accompanying booklet with "site-specific" photographs, brief history of Tilted Arc, and statements by curators.

Also find quotes by Serra, STOREFRONT brochure and bibliography about the Tilted Arc controversy. All articles listed are available at the Midtown Public Library (40th Street and Fifth Ave.), and STORE¬ FRONT .

We wish to hear if you will participate by September 15th. Com¬ pleted works must be delivered to the Clocktower by October 24, 1985. If you need more information please call Tom at (212)344-5425 or STOREFRONT.

David Hammons showed documentation of Shoe Tree, his guerrilla addition of twentyone pairs of shoes thrown over the top of Serra’s “prop sculpture,” TWU. that was across town from the Arc at the time of the show. Hammons’ hightops and platform shoes inscribed a Harlem/Dada sensibility onto Serra’s Downtown/High Modernist work.

He brought Serra into the City and out of the purely structural definition of site. In some ways, his was the most aggressive gesture in the exhibition, in that it was enacted on a real Serra piece in public, rather than confining itself to the safe haven of the gallery. The only other artists who ventured out of the gallery for the show were Bill and Mary Buchen, who created a tape-loop sound collage from interviews they conducted at the Federal Plaza. The level of hostility toward the Arc, and the misunderstanding of the artist’s intentions by the “average person” on the plaza made the tape funny and depressing. One worker thought the piece was a wind baffle. Others thought it was badly in need of a paint job. The tape showed that the “local public’s” opinion of the Arc was almost universally negative. Those in the art world who deny this deeply-felt hostility are fooling themselves.

“This paper examines the indirect confrontation between Richard Serra and David Hammons in a series of performance interventions by Hammons, who acted upon Serra’s 1980 sculpture T.W.U. through, Pissed Off (1981) and Shoetree (1981). Serra’s and Hammons’ relay exposes the synchronicity of their artistic practices in New York while making apparent their stark differences in commitment. The tension between Serra’s burgeoning blue-chip celebrity and Hammons’ underground artistic identity frames one site of struggle between artists committed to political, often racially grounded meaning, and those whose work and its canonization would seem to suppress the commitments of the former. Seeking a more complex mapping of contemporary art history and African American art history, this presentation interrogates both artist’s commitments to experience, phenomenology, materials, the monumental, and their motivation of public space.”

http://ellentani.com/2015/09/29/vandalizing-discourse-richard-serra-and-david-hammons/

In 1981, the artist David Hammons and the photographer Dawoud Bey found themselves at Richard Serra’s T.W.U., a hulking Corten steel monolith installed just the year before in a pregentrified and sparsely populated TriBeCa. No one really knows the details of what happened next, or if there were even details to know aside from what Mr. Bey’s images show: Mr. Hammons, wearing Pumas and a dashiki, standing near the interior of the sculpture, its walls graffitied and pasted over with fliers, urinating on it.

Another image shows Mr. Hammons presenting identification to a mostly bemused police officer. Mr. Bey’s images are funny and mysterious and offer proof of something that came to be known as “Pissed Off” and spoken about like a fable — not exactly photojournalism, but documentation of a certain Hammons mystique. It wasn’t Mr. Hammons’ only act at the site, either. Another Bey image shows a dozen pairs of sneakers Mr. Hammons lobbed over the Serra sculpture’s steel lip, turning it into something resolutely his own.

Soon after he arrived in New York, from Los Angeles, in 1974, Mr. Hammons began his practice of creating work whose simplicity belied its conceptual weight: sculptures rendered from the flotsam of the black experience — barbershop clippings and chicken wing bones and bottle caps bent to resemble cowrie shells — dense with symbolism and the freight of history.

His actions, which some called performances, mostly for lack of a more precise descriptor, were the spiritual stock of Marcel Duchamp and Marcel Broodthaers — wily and barbed ready-made sculptures, created by inverting spent liquor bottles onto branches in empty lots, or slashing open the backs of mink coats, or inviting people to an empty and unlit gallery.

The practice for which Mr. Hammons is best known, perhaps, is his own legend. Not much for holding still, and uninterested in accolades or institutional attention, he cultivated an enigmatic persona predicated as much on conceptual rigor as resistance to public life.

The “Pissed Off” images are several in a suite Mr. Bey made in New York in the early ’80s of Mr. Hammons and other artists as they floated in and around Just Above Midtown, known as JAM, Linda Goode Bryant’s gallery devoted to contemporary African-American artists in a time when few other institutions were providing such a platform. Mr. Bey’s images of Mr. Hammons, which are set to go on view this week in a special section at Frieze devoted to JAM, are striking, not least because they are rarely exhibited, but also because the total visual record of Mr. Hammons and his work in New York is so spare.

Mr. Bey, who was born and raised in Queens, N.Y., and whose own practice has been concerned with ideas of community and the continuum of black life, met Mr. Hammons early in his tenure in New York. Mr. Bey had recently begun photographing street life in Harlem and was showing his images at the Studio Museum of Harlem, where Ms. Bryant was working. When she left to open JAM on 57th Street and Fifth Avenue, Mr. Bey fell in with its circle of artists, many of whom, including Mr. Hammons, Senga Nengudi, and Maren Hassinger, had been working in Los Angeles.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/01/arts/design/dawoud-bey-david-hammons-jam-frieze.html