Please allow 7 working days to process before shipping

White Short Sleeve Tee

100% Combed Ring Spun Cotton

Agnes Denes

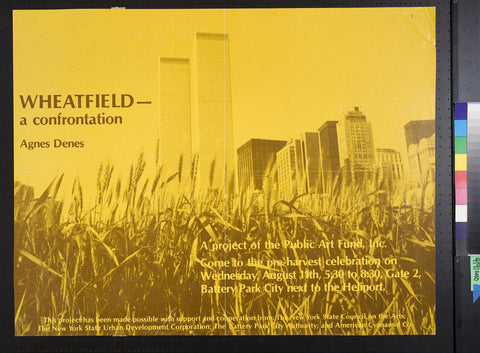

Since the late 1960s, Hungarian-born artist Agnes Denes has created large-scale, public environmental installations including, perhaps most famously, 1982’s Wheatfield—A Confrontation, in which she planted, tended, and harvested a two-acre field of wheat on a landfill in lower Manhattan (which is now Battery Park City), not far from the World Trade Center. It’s a seemingly straightforward piece, lasting only the six months it took to grow and harvest the 1,000 pounds of wheat, but, like much of Denes’s work over her 50-year career, its apparent simplicity hides the heady ideas (and hard physical labor) at its foundation.

The wheatfield stands as a visionary and transgressive act, a monument to identify misplaced priorities questioning controversial global issues and endless contradictions. The provoking work contrasted urban and rural, finance and agriculture, manual labor and artistic value, and also revolutionized the possibilities of public art.

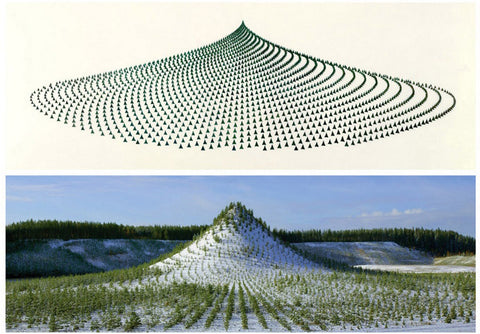

A pioneer of earth art, Denes was born just before earthworks artists like Walter De Maria, Robert Smithson, and Richard Serra. While her work also utilizes the landscape as a site, unlike those artists, Denes’s mathematical forests, rice fields, wheat fields, and pyramids developed alongside the growing environmental movement of the 1970s and an interest in minimizing man’s ecological impact on the natural world.

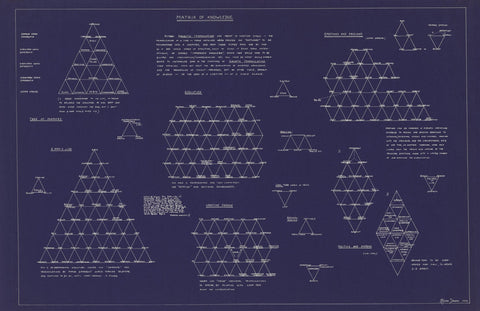

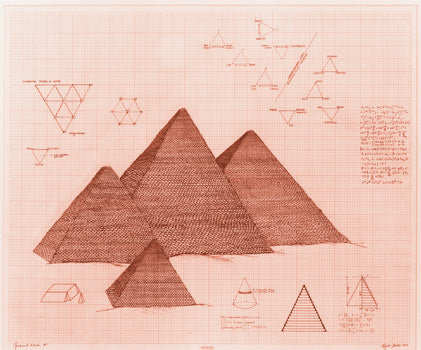

The Pyramids, initiated in 1969, explore, dissect and reshapes the geometric form through the lens of an abstract mathematical theory of probability in order to reveal its logical patterns. This approach later allows the pyramid to become a fluid, floating form that by keeping its geometric perfection offers future possible habitats for living in space or other self-contained environments (Pyramid Awakens, Flying Bird Pyramid – For the New and Future City, Fish Pyramid – Noah’s Ark for the New City, Half-bird Space Station). In these drawings, Agnes Denes has developed an innovative use of metallic dust and ink applied by hand that give an ethereal glow to rigorously calculated patterns.

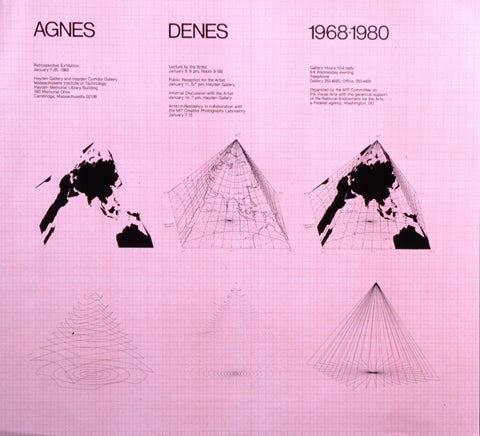

Her series entitled Isometric Systems in Isotropic Space – Map Projections originate from the study of distortion and perspective. Playing with imagination and reality, uncertainty and knowledge, the artist applies mathematical formulae to the form of our globe to reshape it, rearrange its structure, mass, coordinates of longitude and latitude on graph paper into an egg, a snail, a cube or a hot-dog, that all dissolve our rigid lecture of space by investigating the notions of curved space, black holes, fluidity and relativity.

A pioneer of conceptual and environmental art, she has also coined the notion of Eco-Logic to express the paradox – or as she often refers to it, the human predicament – that lays between achievable conditions of global survival and logic, demonstrating how, despite being in its centre, we are prisoners of our own system. In 1968, she authored Rice/Tree/Burial, the first land-art performance with expressed ecological concerns that called for environmental consciousness and responsibility.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles

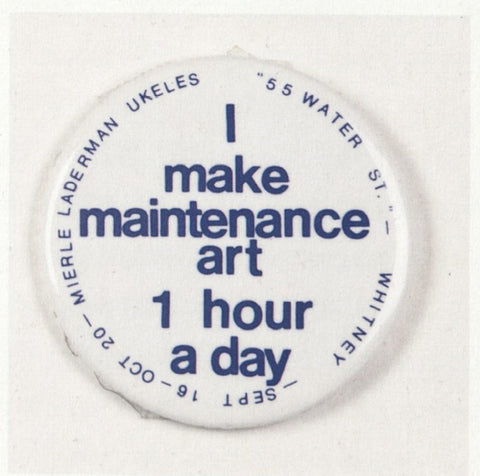

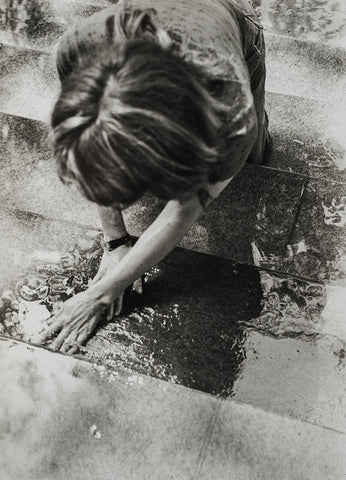

In the 1960's, Mierle Laderman Ukeles made labour a public problem. It had always been her problem: in addition to making art she did all that extra work that makes up the so-called ‘second shift’ of invisible, unvalued, reproductive labour that women do. Her genius was not in her ability to juggle the two supposedly distinct types of labour – which many have done – but in finding a way to do them at the exact same time.

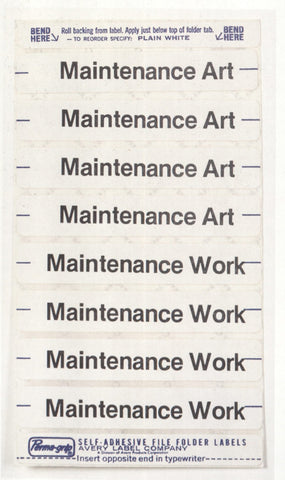

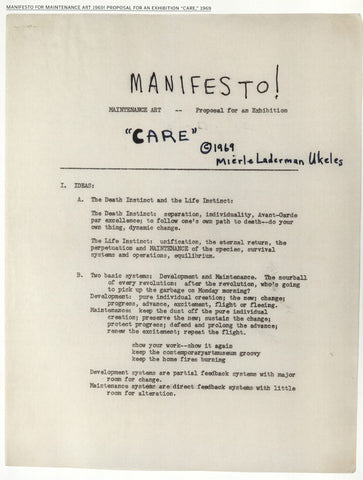

In 1969 Ukeles wrote her now-famous Manifesto for Maintenance Art, a proposal for an exhibition titled ‘Care’. In it she declared that all her normal lifework – what she called ‘maintenance’ – would now be her Art. ‘I do a hell of a lot of washing, cleaning, cooking, renewing, supporting, preserving, etc.’, she wrote. ‘Also (up to now separately) I “do” Art’. For the proposed exhibition, she would perform those activities inside a public art institution, ‘in full public view,’ as process pieces. ‘I will sweep and wax the floors, dust everything, wash the walls (i.e. “floor paintings, dust works, soap-sculpture, wall-paintings”) cook, invite people to eat …’

Ukeles went on to make many maintenance artworks, which regularly involved collaborations with other maintenance workers. Since 1976 she has been the official artist in residence of the New York Sanitation Department. One of her pieces is from a suite of projects she made in 1973 at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum, in Hartford, Connecticut. For Transfer: The Maintenance of the Art Object, she selected an object from the museum’s permanent collection, a female mummy in a glass case, and ceremonially appropriated the cleaning materials from the worker who usually cleaned such cases. She then cleaned the case herself, converting it into a ‘dust painting’, evinced by a stamp she placed on the glass certifying it an ‘Original Maintenance Artwork’.

In the last phase of transition, she gave the cleaning materials to the museum conservator, who was from then on in charge of cleaning the case – producing the final element in the transmutation: ‘a clean Maintenance Artwork’.

In another performance, Keeper of the Keys, Ukeles took the janitor’s keys and locked and unlocked various offices and rooms in the museum. Once Ukeles had locked an office, it became a Maintenance Artwork and no one was permitted to enter or use the room. Keeper of the Keys created an uproar, as it drastically impacted the work lives of the museum’s staff who pleaded to have certain floors exempted from the project so they could work undisturbed. Ukeles’ performances, examples of conceptual art called “Institutional Critique,” surfaced the hidden labor of maintenance in the museum setting, and the subsequent visibility of this labor proved to be incredibly disruptive to the institution of the museum.

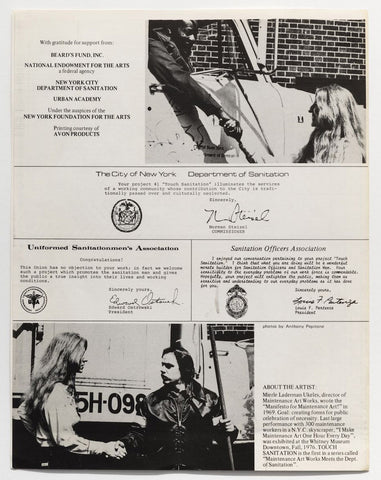

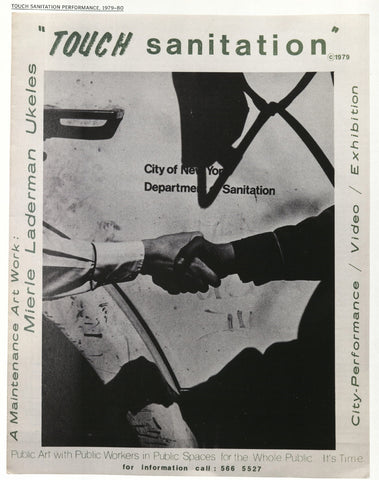

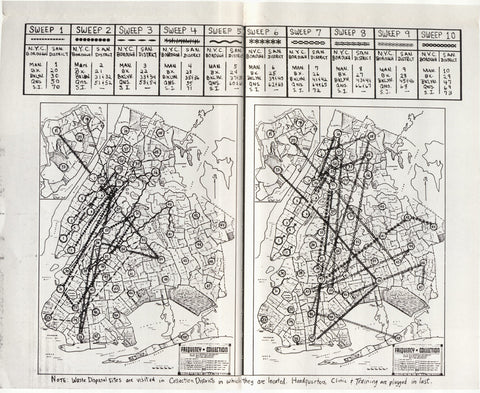

Her “Touch Sanitation” Performance lasted 11 months, with the official support of the Department of Sanitation, Ukeles arrived at 6 a.m. daily at a processing facility to devise a cross-town route that put her in contact with as many “san men” as possible. Aboard a DSNY truck, she swept through the city, stopping to shadow workers at garages, landfills, offices, and street corners. Ukeles physically mirrored the work of these laborers, hauling trash and tromping through dumps. And she grasped the palms of each one, saying: “Thank you for keeping New York City alive.”

Another work included a 20 cubic-yard garbage truck faced with hand-tempered mirrors titled “The Social Mirror” which debuted in the grand finale of the first NYC Art Parade in 1983. According to Ukeles, “This project allowed citizens to see themselves linked with the handlers of their waste.”

Ukeles’s conversion of an ancient artifact to contemporary artwork to historicized object is a form of magic, as is her conversion of worker to artist to worker again. Magic, because the differences between these types of labour are themselves magical constructions: they result from magical thinking about what is valuable and how value transfers from person to object and back.